Content warning: This article contains descriptions of racist abuse

"When the video of George Floyd splayed on the pavement with an American police officer kneeling on his neck appeared on my social media feed in May, it immediately triggered years of pain from racial trauma.

I can vividly recall my first experiences of overt racism here in Australia that occurred before I even reached high school.

I was called a multitude of racial slurs – horrific, hurtful names such as 'ape', 'gorilla', 'chimp', 'beast' and more that I will not offer any more time to. Growing up in Sydney, I was spat on while walking home from school, told to bleach my skin, and had objects and food thrown at me.

My experience is living proof that it’s not just people of colour in America who face this terrible systemic and deadly racism. Every single day, black people like me are dehumanised, brutalised and murdered. Any idea that experiencing racism is a choice is ludicrous and beyond a fallacy. Many black people across the world carry a shared hurt and feeling of invisibility that is very hard to shrug off because each day we are persistently perceived to be outside the 'normal', stuck in a place that makes our emotions void and sees our skin as vile.

Many black people across the world carry a shared hurt and feeling of invisibility that is very hard to shrug off because each day we are persistently perceived to be outside the 'normal', stuck in a place that makes our emotions void and sees our skin as vile.

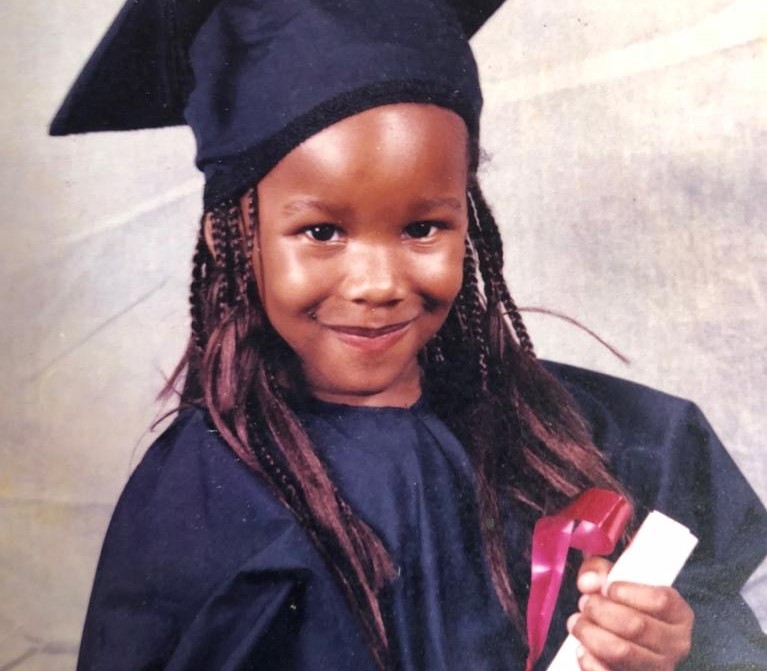

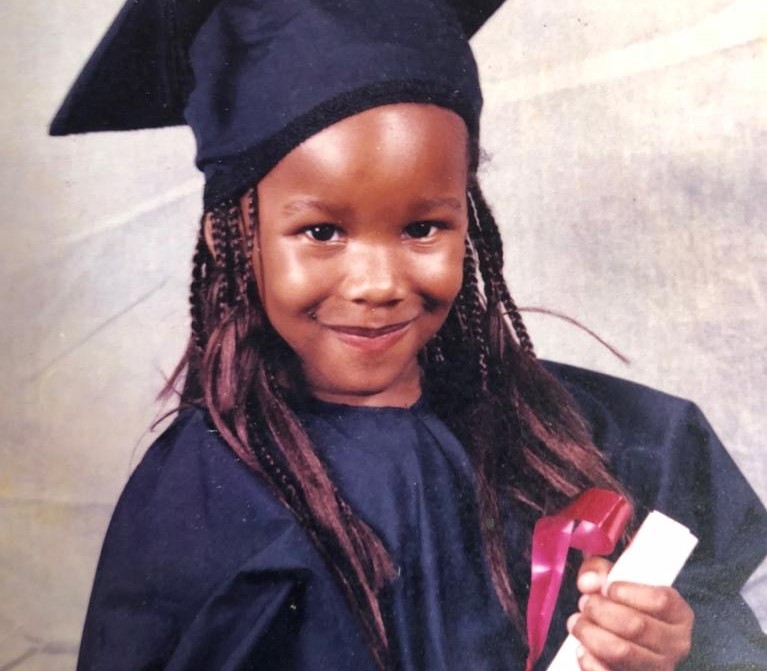

Angelica Ojinnaka as a child. Source: Supplied

As a teenager, I began to clearly understand that I wasn’t accepted by society; a society repulsed by my skin tone. But now, I find myself battling an even more sinister form of racism that I hadn’t yet conceptualised when I was younger – covert racism.

It would be the unintentional or intentional snubs and comments such as saying my natural hair is unprofessional or assuming that I cannot speak English. Being followed in shops, and being denied roles or opportunities are among the many examples I can give.

Experiencing racism is debilitating. While some things may appear to be innocuous, the accumulation of these incidents and micro-aggressions is mentally exhausting.

It’s for this reason that I have always pushed myself to be involved in leadership roles and decision-making; to make room for young black folk like me to have hope.

Research of close to 10,000 girls and young women by the charity for girls’ equality Plan International Australia found 76 per cent aspire to be a leader in their country, community or career.

From being a school captain to engaging in leadership roles within the community and at a tertiary level, many of these activities were seeded from one prominent hope: that if just one young black girl could see me and say, ‘I can hang in and get there too’, then that’s all that matters. But being black and female in leadership roles does make you hyper-visible and vulnerable to attacks on your qualification. Once you have your foot in the door of a room where you are the only representative of your culture, you feel like you have to tread carefully just to be taken seriously.

But being black and female in leadership roles does make you hyper-visible and vulnerable to attacks on your qualification. Once you have your foot in the door of a room where you are the only representative of your culture, you feel like you have to tread carefully just to be taken seriously.

A Black Lives Matter rally in Sydney in July. Source: Getty Images

Currently, there are even people in positions of leadership and power that use dehumanising rhetoric that then manifests into the everyday conception of black people and our abilities, suggesting we don't belong in leadership spaces.

Non-tokenistic diversity in leadership is a gateway to championing issues of inequality and disadvantages, including issues that affect black communities.

For those eight minutes and 46 seconds that George Floyd was filmed being brutally pinned to the ground by police – those who are supposed to protect society – the world was able to see and feel the reality of life for black people (especially First Nations communities in the Australian context): both the crushing nature of anti-blackness and the people that allow such racism to fester.

In the incredible ‘I Can’t Breathe’ episode of the ABC’s Four Corners this month, Stan Grant poignantly described this anti-blackness as something that 'can touch our lives at any time'.

When people shout the racially fuelled ‘All Lives Matter’ rhetoric, they fail to see that the statement is meaningless if we are not seeking to reverse the harrowing brutality and trauma faced by black people.

It has been more than two months since the death of George Floyd, and in that time we’ve seen millions of black people and allies around the world say enough is enough. It sparked some of the biggest and most powerful waves of Black Lives Matter protests the world has ever seen.

I applaud all of those who are coming on board as allies, but allyship needs to be considered a journey and not a stopping point. Allyship is continuously remoulded by confronting difficult truths daily.

What has worked well is when allies stood up against racist slurs when I was not in the room and online, or passed on petitions that have been translated into structural policy changes. Ineffective allyship is evident when there is a great distance between online posturing and offline actions. For example, the hypocrisy we all saw when fashion brands posted a #BlackoutTuesday square but had not addressed racism experienced by their own former staffers and ineffective measures of reporting racism within their workplace structures.

Ineffective allyship is evident when there is a great distance between online posturing and offline actions. For example, the hypocrisy we all saw when fashion brands posted a #BlackoutTuesday square but had not addressed racism experienced by their own former staffers and ineffective measures of reporting racism within their workplace structures.

Angelica Ojinnaka, centre, is calling for practical engagement to support black people in Australia. Source: Supplied

While I do recognise the allyship takes many forms, it should always go hand in hand with empathy. Allies need to be continuously sensitive about what you are standing up for.

My advice is to avoid being hypocritical and performative because it does a disservice to those suffering from racial injustices. Instead, conduct intention research, engage politically within the home and broader communities to be well-informed on this issue.

The burden should not be on black people to educate others about systemic oppression they never asked for. Being an ally against anti-black racism is to recognise that you will never experience the black experience, but you are willing to engage practically to support black people.

Ways of doing so include following informative social media accounts, immersing yourself in literary and audio works on the topic, targeting racism in education systems, and donating to organisations who are led by black communities doing frontline work to support change (if it is within your means).

But, a major step to dismantling systemic racism is to look at our leadership within Australia across all sectors. People who experience anti-black racism need to be given greater opportunities to be involved in leadership (without discrimination), and not just because you want to tick a diversity box.

Young girls and women from diverse backgrounds who are isolated from opportunities because of gender and race should be supported by mentorship schemes, included in youth-led civic action, and accurately represented in the media without negative stereotypes.

With greater cultural diversity of voices in leadership that cut across different intersections, we can hopefully achieve a well-rounded education reform and policy responses to tackling the systemic racism that still, to this day, plagues our society."

Angelica Ojinnaka is a Plan International Australia youth activist based in Sydney.